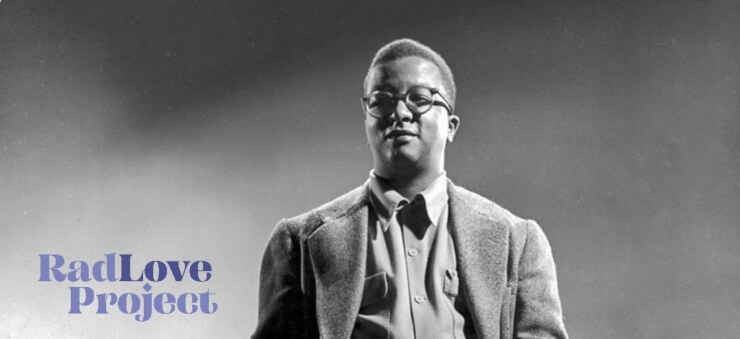

As Kristin and I were discussing content for this month in late March, I noted that April is Jazz Appreciation Month, and that I thought Billy Strayhorn’s life and legacy would be an interesting topic to explore (hopefully you agreed if you read my recent profile–if you haven’t had the chance yet, click here!) As I wrote about Strayhorn’s struggles to gain admission to classical music studies at the collegiate level in Pittsburgh, I was struck by the similarity of both the circumstances and the timing to those of another black musician and composer from Pennsylvania–the inimitable Nina Simone. I decided then that Nina would be a perfect complementary topic to wrap up JAM 2024.

With that said, the legacies of Billy Strayhorn and Nina Simone are different. While he remained largely behind the scenes, seeking recognition only in the form of credit for his work, she was an internationally known performer for decades who spoke directly to the public and the media about her views. Given the extensive scholarship on Nina Simone’s catalog, life and politics that is widely available, it seems another profile isn’t entirely needed; therefore, after briefly setting the stage for Nina Simone’s songs of protest, I’ll focus on a deeper dive into four of her most enduring and impactful compositions, and how they have impacted popular music as well as social justice dialogue.

Background

Celebrated American singer, songwriter, pianist, composer, and arranger Eunice Kathleen Waymon, known professionally as Nina Simone, “the high priestess of soul,” was born in Tryon, North Carolina in 1933. Her mother was a Methodist minister while her father worked as a dry cleaner, barber, and entertainer. The sixth of eight children, she began to play the family’s piano at age four and immediately showed considerable talents. She played regularly at her church, and performed in her first recital at age 12; her parents, seated in the front row, were forced to move to accommodate white attendees. She famously refused to play until her parents regained their seats, an incident she noted influenced her involvement in the civil rights movement.

Thanks to the advocacy of her teachers and financial support from the community, Eunice attended Allen School for Girls in Asheville, North Carolina. Following her graduation in 1950, she spent the summer studying with Carl Friedburg of the Juilliard School, preparing under his guidance for an audition at Philadelphia’s renowned Curtis Institute of Music. Eunice was denied admission to Curtis, a blow to her own aspirations as a classical musician, and to her family that had just moved to Philadelphia to support her. Throughout her life, she stated plainly her belief that she was not admitted to Curtis due to her race. She continued her studies privately with Curtis professor Vladimir Sokoloff, but never reapplied to the school.

It was these private lessons with Sokoloff that would lead to Eunice’s adoption of a professional moniker, which would eventually be known worldwide. To fund her tuition, she began to play popular music at the Midtown Bar & Grill in Atlantic City. Knowing her mother would disapprove of this, she adopted the stage name Nina Simone to obscure her identity–“Nina” was a nickname from a childhood boyfriend, and “Simone” referenced the French actress Simone Signoret. Despite her lack of interest in singing, the owner insisted on this, launching her career as a jazz vocalist. As Nina Simone, her performances incorporated jazz, blues, and classical music; it was at the Midtown she would gain her first loyal fans.

Over the next decade, Nina became a commercial success following the 1958 release of top 20 single “I Loves You, Porgy” and her 1959 album Little Girl Blue. She continued to release successful live and studio albums in order to fund her ongoing classical music studies, but she was indifferent about playing pop music and remained ambivalent towards the recording industry throughout her career.

A change in record labels in 1964 would lead to a shift in her creative output that would permanently alter the course of her career and life. Though her performances had long included songs that spoke to her experience as a Black woman, her first album on the Phillips label, Nina Simone in Concert, featured the original song, “Missisippi Goddam,” her first musical expression on racial inequality in America.

“Mississippi Goddam”

Composed by Simone in less than an hour in response to the murders of Emmitt Till and Medgar Evers, as well as the 16th St Baptist Church bombing in neighboring Alabama, “Mississippi Goddam” was first performed at the Village Gate nightclub in early 1964. In March if that year, she performed it at Carnegie Hall for a predominantly white audience; she notes sardonically that the song is “a show tune, but the show hasn’t been written for it yet.” The recording of this performance was included on Nina Simone in Concert, a compilation of her 1964 Carnegie Hall appearances. The single would gain wide recognition as an anthem of the civil rights movement.

Backlash to the song’s release was immediate. It was banned outright in some states; in others, radio stations destroyed promo singles and returned the broken records to the label. She famously performed the song on the Steve Allen Show in September of 1964, with Allen remarking prior to the performance that he knew it would inspire “a lively discussion about censorship.”

In addition to its role in the civil rights movement, the song’s cultural impact has been widely recognized in recent years:

- In 2019, it was chosen by the Library of Congress for preservation in the National Recording Registry for being “culturally, historically, or aesthetically significant”

- In 2021, it was listed as #172 on Rolling Stone’s “Top 500 Songs of All Time”

- In 2022, American Songwriter ranked it #3 on its list of the 10 greatest Nina Simone songs

- In 2023, the Guardian ranked it #1 on their list of the 20 greatest Nina Simone songs

“Four Women”

On her 1966 album Wild is the Wind, Simone’s social commentary was again highlighted in the song “Four Women,” which tells the story of four African American, each representing a common stereotype:

- Aunt Sarah, who represents the strength and resilience of enslaved African Americans

- Saffronia, a mixed race woman who represents Black people’s suffering at the hands of powerful white people

- Sweet Thing, a prostitute

- A woman hardened and embittered by the generational suffering of Black people in America, revealed to be named Peaches in the song’s finale

In the Village Voice, Thulani Davis described the song as “an instantly accessible analysis of the damning legacy of slavery, that made iconographic the real women we knew and would become.” To Simone’s great dismay, her effort to highlight injustice and the suffering of African Americans in “Four Women” was deemed racist by some who believed it drew on harmful stereotypes, resulting in another radio ban.

The song has been widely covered by groups ranging from English blues rock band Black Cat Bones to Jamaican musician Queen Ifrica. It was sampled in Jay-Z’s 2017 song “The Story of O.J.” and has received both theatrical and film treatments.

“Ain’t Got No, I Got Life”

Technically a medley of two songs from the Broadway musical HAIR, “Ain’t Got No, I Got Life” was described by Yale musicologist Daphne Brooks as “a new Black anthem–a wholly original” reimagining and interpolation of the original material that created a “trademark” protest song mirroring the profound cultural impact of “Mississippi Goddam.” It reached #2 in the UK and #1 in the Netherlands, also charting on the Billboard Hot 100 in the U.S., peaking at #94. The success of this tune exposed a younger generation to Simone, and accordingly it became a standard in her repertoire.

Simone recorded two distinct versions–the first a jazz interpretation with a repeated piano hook, the second in a rock style with guitar and horn features. Both have been popularized in recent advertising campaigns.

On the 1969 live album Black Gold live album, Simone brings the song to a false ending, inviting applause, then continuing on. Vanderbilt University Professor Emily Lordi said, “This is a technique from the gospel playbook, and its effect is to indicate that the rest of the performance is running on reserves of spirit—an effect she will also produce when she sings the last word.”

A live performance of the song is a pinnacle moment in the 2015 documentary film, What Happened, Ms. Simone?

“To Be Young, Gifted, and Black”

A collaboration with Weldon Irvine that paid tribute to Lorraine Hansberry’s autobiographical play of the same name, Simone first performed “To Be Young, Gifted, and Black” for a crowd of 50,000 attendees at the 1969 Harlem Cultural Festival, which was featured in the 2021 documentary film Summer of Soul.

Two months later, she recorded the song in a live concert at Philharmonic Hall that would become the Black Gold album. Released as a single in January 1970, Simone again charted on the Billboard Hot 100, reaching #76 as well as #8 on the R&B charts. It is widely considered an anthem of the Civil Rights Movement and is regarded as one of Simone’s most impactful songs.

The song has been covered extensively by artists including Aretha Franklin (on her 1972 album of the same name), Elton John, and Mechell Ndegeocello, and has been sampled by Rah Digga, Faith Evans, and Rapsody.

Impact

Despite the influence of her protest songs and activism, Simone expressed regret about their effect on her career. She believed the release of “Mississippi Goddam” and the ensuing radio boycotts irreparably harmed her public perception. She also felt several of her albums were effectively boycotted by her label’s failure to promote them.

Simone spent the final decade of her life in France, taking up residence in Carry-le-Rouet in 1993, the year her final album A Single Woman was released. She died at home in her sleep on April 21, 2003 following a multi-year battle with breast cancer. Following a funeral service in a local parish that was attended by luminaries including Patti LaBelle and Ruby Dee, her ashes were scattered across the continent of Africa.

Nina Simone’s essence was captured perfectly in 1970 by the American poet Maya Angelou, who wrote of her “She is loved or feared, adored or disliked, but few who have met her music or glimpsed her soul react with moderation.” More than fifty years later this sentiment remains true; Nina Simone’s impactful legacy continues to inform and provoke thought, even today.

Again, it’s been nice to temporarily step away from commentary on the 2024 election to focus on arts, history, and activism. If you’ve enjoyed reading this, do us a favor and give it a share on your favorite social media platform!

Join the RadLove movement and help us redefine what is possible.

Sign up for our newsletter and follow us on instagram and spoutible!