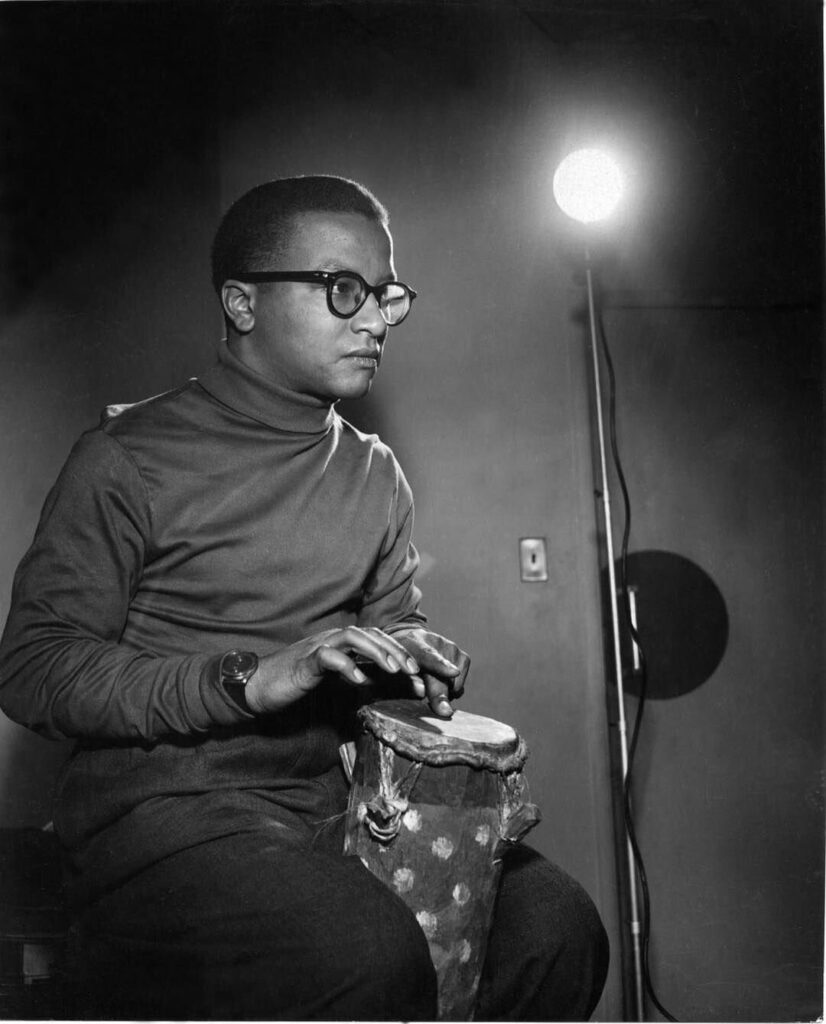

Happy April, RadLove readers! While November 5th is at the forefront of all our minds now that we’re in the thick of election season, our mission at Radical Love Project also includes covering important cultural topics outside the political sphere. With that in mind, in celebration of Jazz Appreciation Month, I’m glad to share something from my background as a professional musician – a profile of pianist, composer, and arranger Billy Strayhorn, a longtime collaborator of Duke Ellington and a legend in his own right who has been recognized and celebrated as a queer icon in recent decades following scholarly inquiry into his life and creative output. I am deeply grateful for the work of Strayhorn scholar David Hajdu, whose exhaustively researched 1996 book Lush Life: A Biography of Billy Strayhorn was a primary source for today’s post.

An equally skilled pianist, lyricist, and orchestrator, Strayhorn is most widely known for his longtime collaboration with bandleader Duke Ellington. Strayhorn was a ground-breaking innovator in the jazz idiom who inspired his contemporaries with forward-thinking melodies, lyrics, and orchestrations. Strayhorn’s compositions have contributed directly to the development of modern jazz and are recognized as quintessential examples of the Great American Songbook, “America’s classical music.”

William Thomas Strayhorn was born in the Rust Belt city of Dayton, Ohio in November of 1915. Though the family moved to Pittsburgh early in his life, he was sent by his mother to live with his grandparents in Hillsborough, North Carolina to avoid the repercussions of his father’s substance abuse, spending the majority of his time there through age ten. Billy’s interest in music first appeared during his years in Hillsborough, where he would listen to records on his grandmother’s Victrola and play church hymns at her piano.

Strayhorn returned to his parents’ home in Pittsburgh, where he began piano studies with Charlotte Enty Cantin, who was accompanist to singer Lena Horne, an African-American singer he would maintain close personal and professional ties to throughout his life. He studied at the Pittsburgh Music Institute and by age 19 was making radio appearances presenting his own compositions – including “Life is Lonely,” which was later named “Lush Life” and would eventually gain universal acclaim as one of the greatest jazz compositions of all time.

Though Strayhorn hoped to become a classical composer, racism prevalent in Predominantly White Institutions prevented him from pursuing such studies at the collegiate level. (At nearly the same time, another legendary Black artist was receiving similar treatment elsewhere in Pennsylvania, as pianist, composer, and vocalist Nina Simone was denied admission to Philadelphia’s Curtis Institute of Music despite her noted gifts.) He became associated with prominent Black pianists including Art Tatum and Teddy Wilson, who introduced him to jazz techniques and guided his development.

Strayhorn’s life-changing exposure to Duke Ellington began when “the Duke” played Pittsburgh with his orchestra in 1933. When Ellington returned in 1938, Strayhorn was able to arrange a meeting during his visit; Strayhorn impressed the legend by explaining to Ellington how he would orchestrate one of his compositions. Thus began a close and somewhat complicated collaboration that would extend across several decades and produce some of the most iconic works ever created in the jazz medium.

Following their meeting, Ellington took Strayhorn under his wing. In advance of his 1939 tour of Europe, Ellington informed his family that Strayhorn “is staying with us.” Strayhorn would meet his first partner, musician Aaron Bridgers, through Ellington’s son Mercer. Strayhorn was openly gay with Ellington and the members of his orchestra, who generally supported and accepted but were sensitive to widely held opinions about homosexuality.

It is now understood that during their nearly three decades of musical partnership, Strayhorn wrote about 40% of repertoire that was credited to Ellington. For more than a quarter century, Strayhorn was nearly always with Ellington at the piano, on commercial releases and radio broadcasts and in the recording studio. His influence had a profound impact on Ellington’s musical identity and commercial success, as those decades are arguably Ellington’s most innovative and adventurous period. According to Ellington, during their many years of collaboration Strayhorn “was my right arm, my left arm, all the eyes in the back of my head, my brain waves in his head, and his in mine.”

Ellington served as a father figure and was protective of the diminutive and mild-mannered Strayhorn, nicknamed by the band “Strays”, “Weely”, and “Swee’ Pea”. Strayhorn’s compositional sensibilities and innate creativity helped the Duke to complete his musical thoughts and introduce new ideas. Though Ellington often took credit for Strayhorn’s charts and compositions, he was also known to joke from the stage “Strayhorn does a lot of the work, but I get to take all the bows!” Humor aside, it is well documented that Ellington allowed his publicists to frequently credit him without any mention of Strayhorn. While he was able to hide his dissatisfaction, Strayhorn revealed to his friends “a deepening well of unease about his lack of public recognition as Ellington’s prominence grew” that would persist throughout their relationship.

The inconsistency around proper attribution was a frustration for Strayhorn. He received credit for work including “Lotus Blossom,” “Chelsea Bridge,” and “Rain Check,” while titles such as “Day Dream” and “Something to Live For”, were listed as collaborations with Ellington. In the case of “Satin Doll” and “Sugar Hill Penthouse”, Ellington alone was credited for a work composed entirely by Strayhorn.

In the 1950s, Strayhorn left the Ellington orchestra for several years to pursue a solo career. Upon rejoining forces, past contention about attribution improved. As the scope of their shared creative output increased, Strayhorn was given full credit as an equal collaborator on later, larger works including Such Sweet Thunder, A Drum Is a Woman, The Perfume Suite, and Far East Suite. Film historians recognize the soundtrack Ellington and Strayhorn composed for the 1959 film Anatomy of a Murder as “a landmark – the first significant Hollywood film music by African Americans comprising non-diegetic music, that is, music whose source is not visible or implied by action in the film, like an on-screen band.” The following year, the Duke and Strays collaborated on the album The Nutcracker Suite, featuring jazz interpretations of Tchaikovsky’s “The Nutcracker”; the front album cover notably includes Strayhorn’s name and picture alongside Ellington.

In addition to his influence upon the sphere of jazz, in the 1960s Strayhorn became an active participant in the civil rights movement. He joined forces with influential friends and allies like his former Pittsburgh collaborator Lena Horne to promote social justice campaigns and fundraisers. Horne and Strayhorn would remain close for the remainder of their lives; though her romantic affections were not reciprocated, Horne considered Strayhorn the love of her life and wished to marry him. Strayhorn was a friend of Martin Luther King, Jr. and was known to occasionally accompany his private speeches. He both arranged and conducted the Ellington orchestra’s rendition of “King Fit the Battle of Alabama” for the My People album and historical review, which were dedicated to King.

In 1964, at the age of 49, Billy Strayhorn was diagnosed with esophageal cancer. Though he persisted and continued to create for nearly three years, he passed away on May 31, 1967. At the time of his passing, Strayhorn was with his partner, Bill Grove; though he was widely reported to have died in Lena Horne’s arms, she was in fact touring Europe at the time.

During Strayhorn’s final days in the hospital, he completed his final composition, “Blood Count,” which became the third track on …And His Mother Called Him Bill, the Ellington orchestra’s tribute album for Strayhorn, recorded shortly after his passing. The album’s final track is a solo performance by Ellington of Strayhorn’s “Lotus Blossom,” a single-take recording captured while the orchestra packed up in the background.

Duke Ellington would continue to promote Strayhorn’s legacy in the years following his passing. In a spoken word passage of his legendary Second Sacred Concert at the Cathedral of St. John the Divine in 1968, Ellington honored Strayhorn by offering his “four major moral freedoms”:

- “Freedom from hate, unconditionally;

- Freedom from self-pity (even through all the pain and bad news);

- Freedom from fear of possibly doing something that might possibly help another more than it might himself;

- Freedom from the kind of pride that might make a man think that he was better than his brother or neighbor.”

Strayhorn’s life and creative legacy were defined by courage and freedom – the courage and freedom to create new harmonic landscapes in the jazz form, the courage and freedom to live fully as a Black gay man in the pre-Civil Rights era, and the courage and freedom to play a prominent role in that fight. The breadth of his musical legacy, for so long diminished, continues to gain recognition, and he stands alongside his longtime collaborator Duke Ellington as one of the most prolific and influential contributors to the history of the jazz art form.

Though this list is by no means exhaustive, some of Strayhorn’s most iconic compositions include:

“Something To Live For” (1937)

“A Flower Is A Lovesome Thing” (1939)

“The Star-Crossed Lovers” (1956)

“The Nutcracker Suite” (1960):

Join the RadLove movement and help us redefine what is possible.